CHRISTIAN MERCAT ET MICHÈLE ARTIGUE

Friezes and tilings frequently accompany the teaching of isometries. The objects that we will consider in this vignette, like the one in Figure 1, are not far from them. However, their understanding involves other mathematics: topology and the theory of graphs, which are more recent than geometry. They constitute a fabulous subject to makes you feel and experience the power of mathematics, its delicacy and rigor.

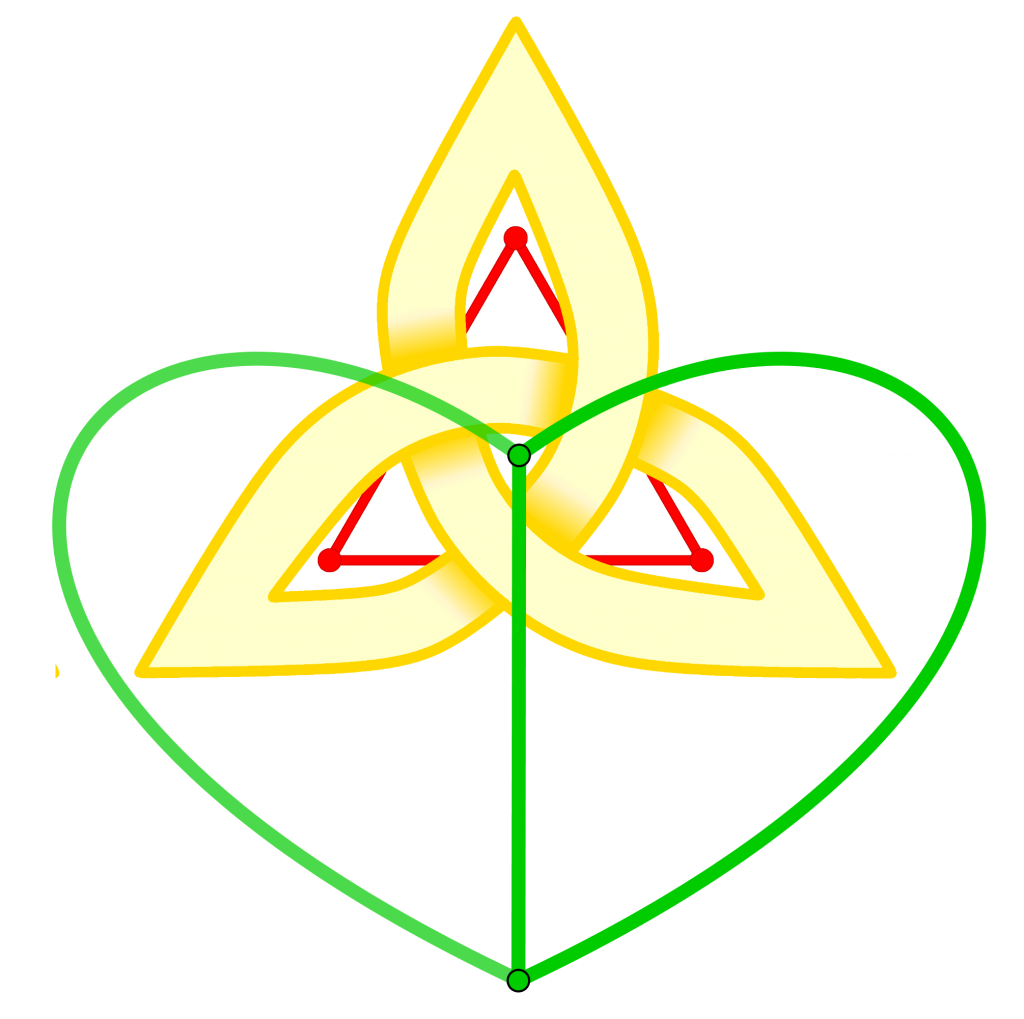

Knots and links have been used in many civilizations as tools and ornaments, from Celtic epic sculptures to Persian illuminations of the Koran (Figure 2).›

They appear in the lives of fishermen and basket makers, and when we lace our shoes or braid our hair. They are extremely diverse and mathematics can help to order this diversity, by questioning what brings together or differentiates these shapes. This study is part of topology and in particular the branch of topology called knot theory.

Knot Theory

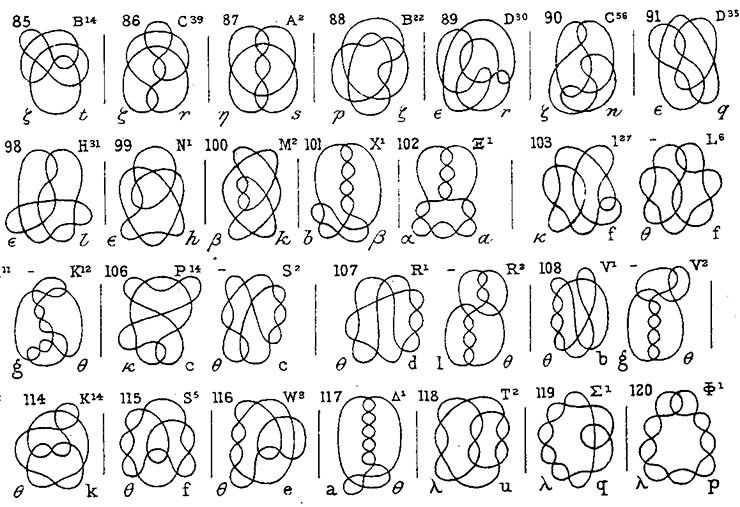

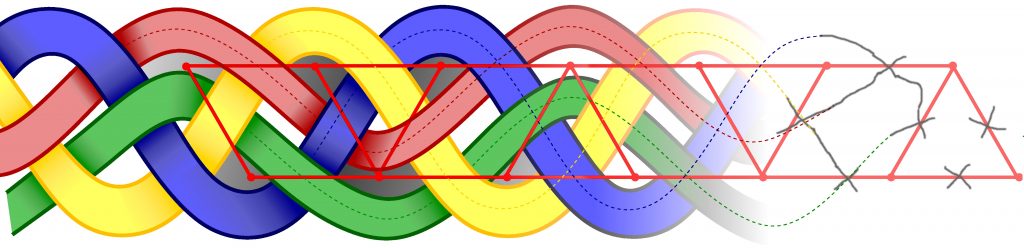

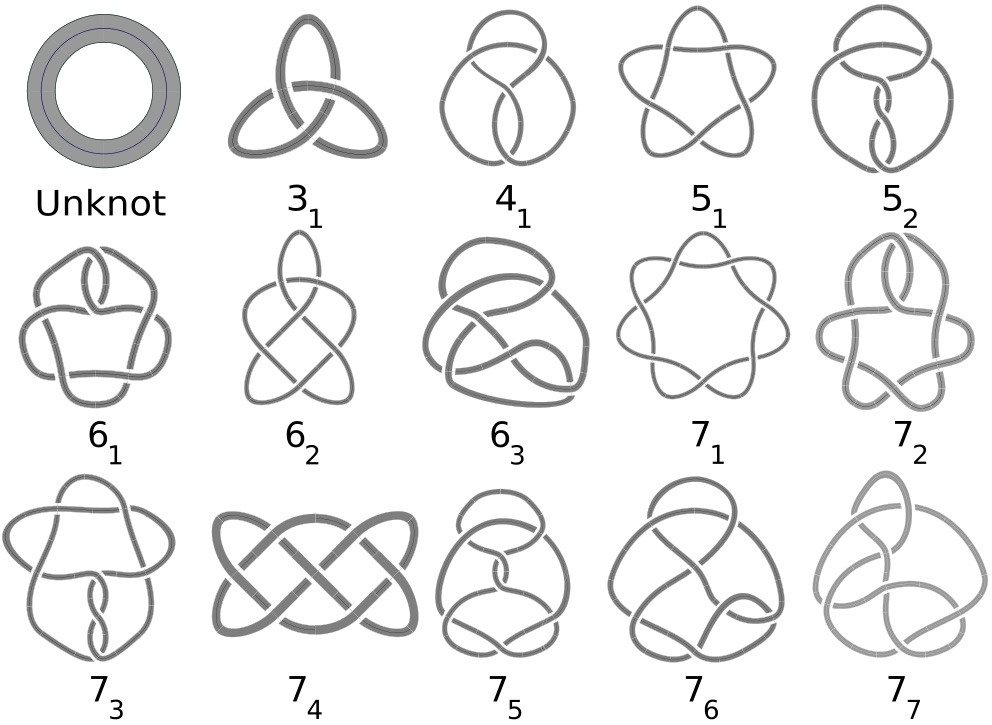

A knot is defined mathematically as an embedding of the circle in space. Practically, imagine a piece of string that we twist without cutting it, and retie the two ends. A link, on the other hand, is an assembly of several knots, several pieces of string. The illustration at the beginning of this vignette, for example, interlaces blue, red, yellow and green ribbons that pass over and under each other alternatively; it’s a braid. The theory of knots began to develop in the second half of the 19th century and its source is not strictly speaking mathematical. Physicists William THOMSON, better known as Lord KELVIN, and Peter Guthrie TAIT were among the first to contribute. They thought it would help them understand the phenomena of absorption and emission of light by atoms. And it lead TAIT to undertake a classification of knots (Figure 3).

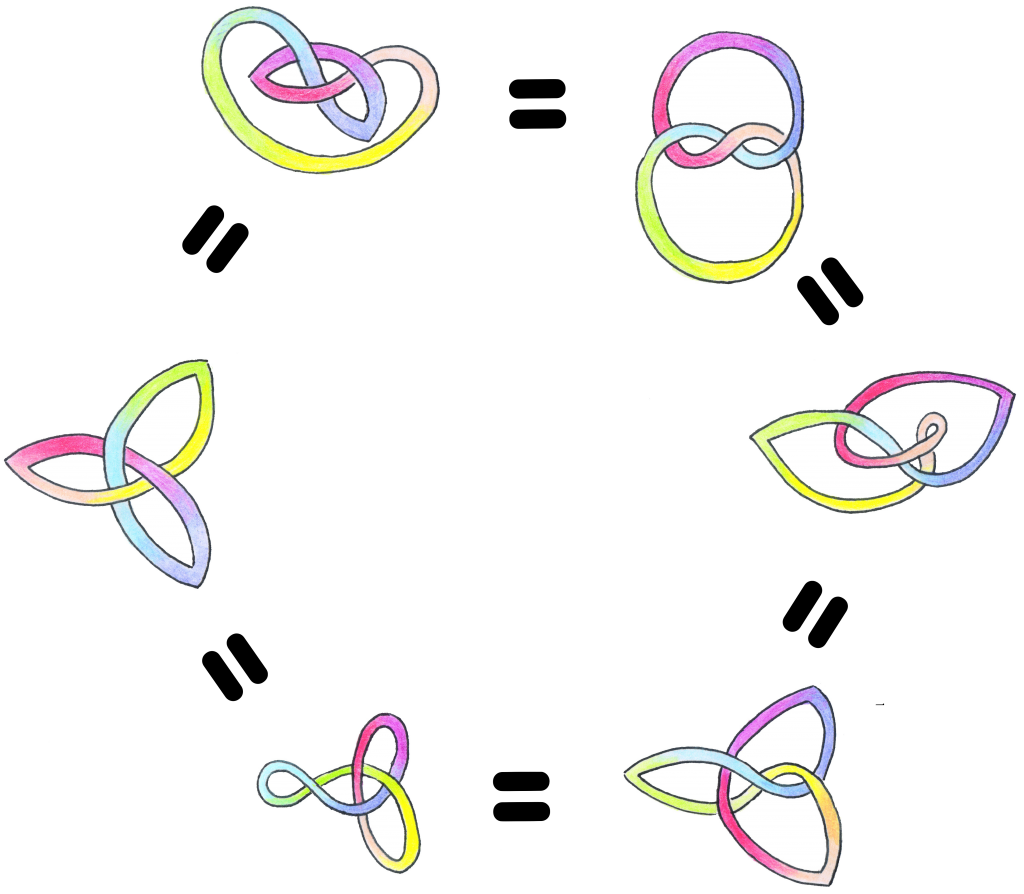

It is difficult to recognize that two knots are in the same class, i.e. that one can pass from one to the other by a continuous deformation, like when trying to untangle a string tied at its ends, without unraveling or cutting it. See for example these different images of the same trefoil knot (Figure 4), which is the simplest knot that is not trivial (i.e. which cannot be reduced to a circle).

This is why knot theory seeks to associate knots with quantities that these continuous deformations do not modify: invariants. For example, the polynomial of ALEXANDER is an invariant which associates a polynomial with integer coefficients to each type of knot. It was discovered by James Wadell ALEXANDER in 1923 and is the first invariant of this type. The ALEXANDER’s polynomial of the trefoil knot, for example, is: ![]() . But first let’s learn how to draw a link. We will then come back to this question of invariants.

. But first let’s learn how to draw a link. We will then come back to this question of invariants.

Links, Knots, and Graphs

A link (or a braid if it is open) is a knot with several components. It is generally represented by its regular projection in a plane: Its threads are drawn crossing transversely and at most two by two: there are not three points of the knot which are projected on the same point of the plane, the strands at the crossings have different projected directions, and the crosses are finite in number. To describe the object that results from these different crossings and its structure is not obvious.

This abstract model neglects a certain number of parameters such as the color of the strands and their thickness. It is a planar graph: with vertices connected by edges, not necessarily rectilinear, which do not intersect and we will label them with a left / right chirality.

A regular projection of a link partitions the plane in different zones, delimited by the projection of the link itself. Where there are crossings, four zones meet locally. We can, according to JORDAN’s theorem,1 color all areas in two colors, say black and white, such that these crosses resemble a chessboard (two opposite zones have the same color and two contiguous zones have a different color).

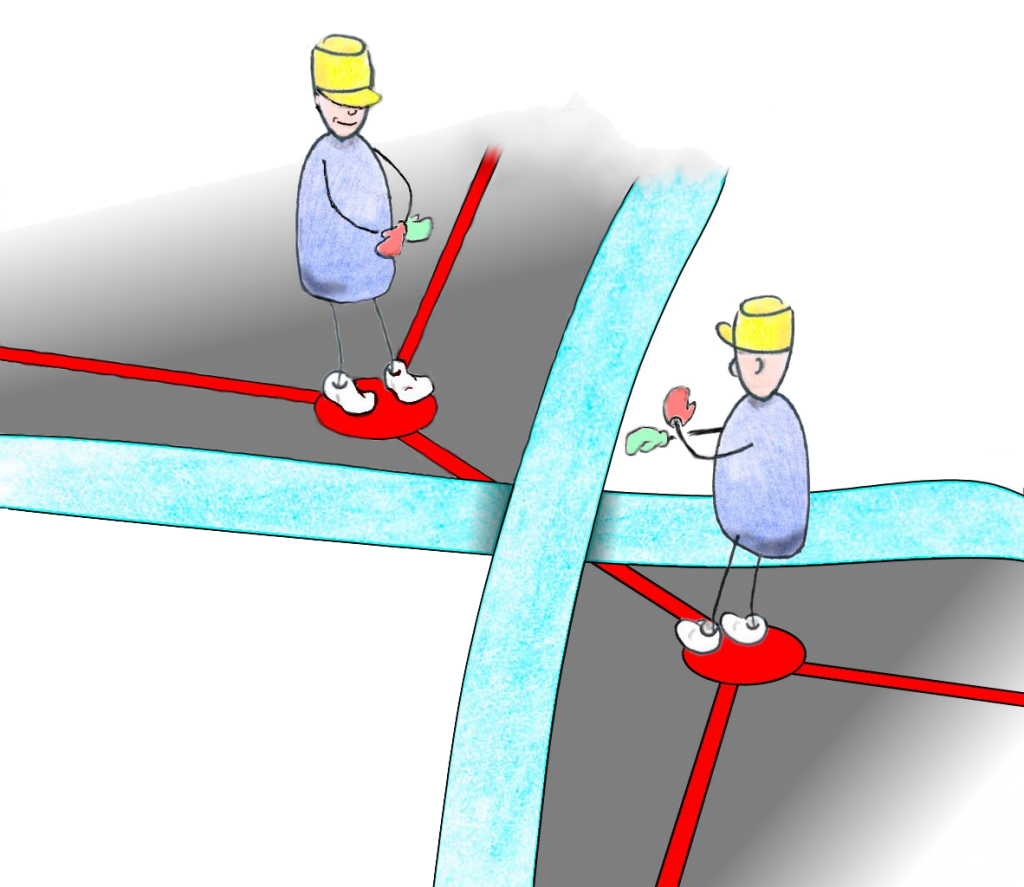

It suffices to decide that the infinite exterior zone is white, to choose a point inside and connect each zone by a path which crosses transversely the projection of the interlacing and avoids crossings (Figure 5).

Each time you go through a thread, you change color. We show that the result does not depend on the chosen starting point, nor on the detail of the path followed and that we always end up with a consistent coloring. The coloring indeed depends only on the parity of the number of strands crossed. We associate a vertex with each black zone and we connect them by an edge, drawn above each crossing, from a black area to its opposite. We then attach the corresponding label to encode whether it is the right strand or the left strand which, seen from a vertex, passes above. The coding is consistent: the opposite zone gives the same chirality (Figure 6).

The trefoil knot is thus associated with a triangle where all edges have the same chirality, say left: it is an alternating link: when you follow a strand, it crosses alternately above, below, above … But this is not the only graph which codes this knot, there is also a graph with two vertices and three edges. They are not straight but curved and labeled right! (Figure 7).

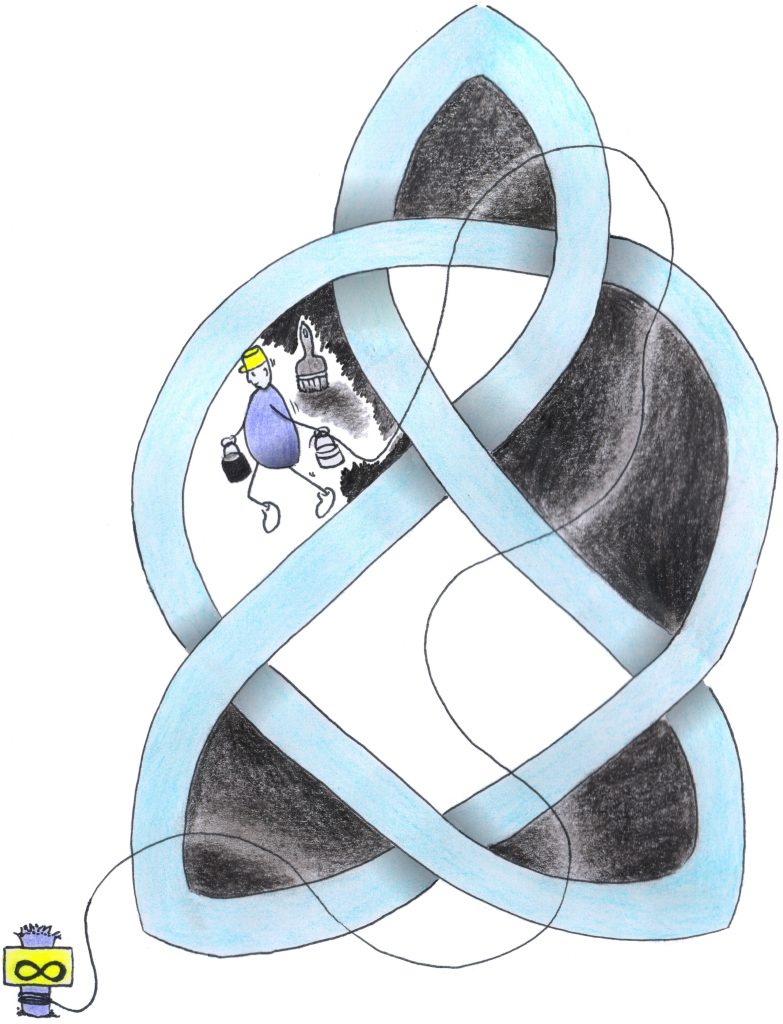

These two graphs are what are called dual graphs. This coding by a planar graph allows the interlacing to be completely coded and it is much easier to describe. The complicated braid is in fact encoded by a graph that can be explained in one sentence, for example, “a triangular ladder from which a rung is removed every three” (Figure 8).

These graphs are evocative and Alexander GROTHENDIECK called a large class of (locally) planar graphs children’s drawings . After this phase of analysis, let’s proceed to the synthesis: draw the interlacing encoded by a graph. This is done in three steps shown from right to left in Figure 8:

- Draw a cross in the middle of each edge. Any cross is in the middle of an edge.

- Connect the strands to each other in a continuous path.

- Decide the above/below.

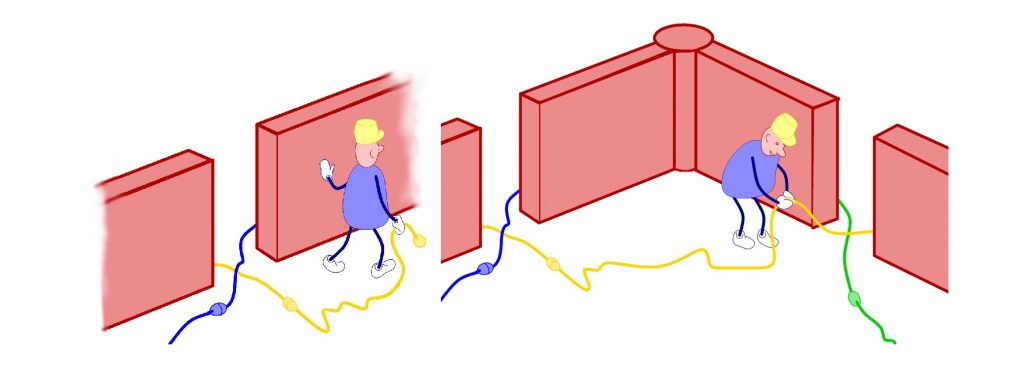

In detail, a cross is drawn in pencil, inclined between 30 and 60° with the edge. This orientation is important for the next stage because we continue each small strand along the ridge in the direction where it points. We thus arrive at the next crossing and we connect to the strand that points in that direction. At this stage, we do not introduce any new crossing and the strands do not cross the edges except at crossings. A useful metaphor: imagine the edges like the walls of a labyrinth, which we follow and which we cannot cross, except at crossroads, where a door appears (Figure 9).

Finally, choosing a crossing, by aligning the edge that carries it with one’s gaze, identify which of the two strands comes from the right and which comes from the left. It allows you to replace the crossing by a “bridge” with a strand (say the left) passing above and the other (the right) below. We invite you now, before reading the rest, to draw up a small graph, of 5 or 6 edges, all of comparable lengths, angles not too sharp not too obtuse, and to develop the knot that it encodes. It suffices for this to play with planar graphs. The video http://video.math.cnrs.fr/entrelacs/ and the examples in [4, 5] can give you ideas.

3. Invariants

The first to take a serious interest in invariants was the young Carl Friedrich GAUSS at the beginning of the 19th century, describing the interlacing of two curves, ![]() , in space, calculated as an impressive though integer valued integral,

, in space, calculated as an impressive though integer valued integral,

![]()

This number is not calculated here from the projection of the interlacing but remains the same when we deform the curves without intersecting. It seems understandable if we are convinced that the result is an integer: the formula depends continuously on each curve and can only jump one unit when there is a problem: when the denominator vanishes, that is, when both curves intersect. But we can calculate it much more easily using a projection, by orienting the strands and simply summing signs for each crossing between the two curves: +1 for ![]() and -1 for

and -1 for ![]() . When there is only one curve, this combinatorial sum defines a number, that we call the writhe

. When there is only one curve, this combinatorial sum defines a number, that we call the writhe ![]() of the projection of the node

of the projection of the node ![]() . The right trefoil knot thus has a +3 writhe. But what becomes of

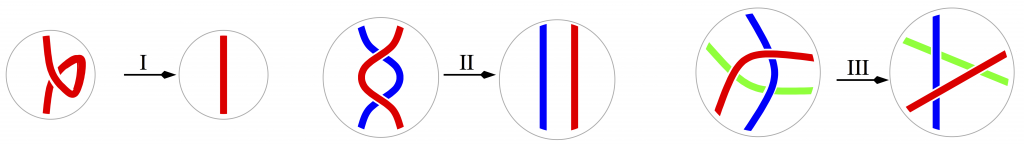

. The right trefoil knot thus has a +3 writhe. But what becomes of ![]() when incidents alter the projection? There are three types of complications which can occur in the projection of a knot. Let’s look locally in a small disc, the rest of the interlacing remaining the same as in Figure 10:

when incidents alter the projection? There are three types of complications which can occur in the projection of a knot. Let’s look locally in a small disc, the rest of the interlacing remaining the same as in Figure 10:

In the twenties, BRIGGS and REIDEMEISTER demonstrated that the only simplifications we needed to go from one particular projection to any other were described by these three movements. To have a knot invariant is therefore to have a function whose value is not modified by these moves. But we quickly see that, whatever the strand orientations, if transformations II and III do not modify the writhe, the first one modifies it! The number ![]() is therefore not a knot invariant!

is therefore not a knot invariant!

However we can fix these problems and get real invariants. They are not simple numbers, but a collection of numbers, coefficients of polynomials in one or two variables.

The heroes of this part of the story are James Waddell ALEXANDER in 1923, John Horton CONWAY in 1969, Vaughan JONES in 1984 and Louis KAUFFMAN in 1987. They discovered, and others after them, by means touching algebra or mathematical physics, ways of building complex links functions as combinations of the same function but on simpler links: these are the skein relations. Among these functions, some are invariants. There are different versions on the same theme. In the same way as for the movements of REIDEMEISTER, we modify locally a link inside a small ball, leaving the rest unchanged.

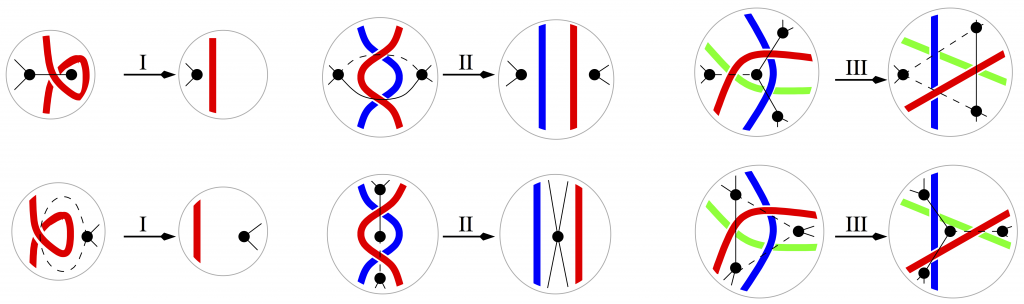

KAUFFMAN’s bracket is defined by

- its value

on the trivial knot,

on the trivial knot, - its value with an extra unknot

and

and -

the skein relation

.

.

And every time we writhe, we multiply the result by that factor. Therefore, when we multiply by ![]() , we get a true invariant! In the box below we calculate the KAUFMANN’s bracket of the standard trefoil knot of writhe

, we get a true invariant! In the box below we calculate the KAUFMANN’s bracket of the standard trefoil knot of writhe ![]() . The crossings that are to be split are indicated by yellow discs.

. The crossings that are to be split are indicated by yellow discs.

that we replace above to yield

We could also have applied three times the skein relations without thinking to obtain

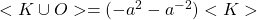

REIDEMEISTER moves and skein movements are also expressed on the graphs which code them (Figure 11 drawing in solid left edges, and in dashed right edges).

On the graph, the skein relations amount to erasing the edge or fusing the vertices, which can be noted by crossing out the edge, respectively across or along. To the skein relation

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

corresponds

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ,

,

each type of wall bringing a factor ![]() or

or ![]() . In applying the relation on all the edges we end up with a disjoint union of trivial knots. Thus, the computation of KAUFMANN’s bracket of the trefoil can also be written:

. In applying the relation on all the edges we end up with a disjoint union of trivial knots. Thus, the computation of KAUFMANN’s bracket of the trefoil can also be written:

It is actually the KAUFFMAN’s bracket of the mirror trefoil.

This sum on all the possible contributions of local configurations is called a partition function in statistical mechanics.

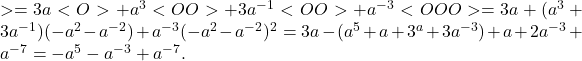

The HOMFLY-PT polynomial2 of a knot ![]() is a little more elaborate, it requires that we orient the knot and needs two variables;

is a little more elaborate, it requires that we orient the knot and needs two variables; ![]() is thus defined by:

is thus defined by: ![]() and the skein relation

and the skein relation

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() . It has the big advantage of being compatible with the COMPOSITION of knots: the sum

. It has the big advantage of being compatible with the COMPOSITION of knots: the sum ![]() of two knots is obtained simply by opening them and gluing them back together. The polynomial of

of two knots is obtained simply by opening them and gluing them back together. The polynomial of ![]() then satisfies

then satisfies ![]() . Just as any integer can be decomposed as factors of prime numbers (

. Just as any integer can be decomposed as factors of prime numbers (![]() ), knots can uniquely decompose into prime knots. It was the chemical intuition of KELVIN and TAIT. Figure lists the first prime knots with up to seven crossings;

), knots can uniquely decompose into prime knots. It was the chemical intuition of KELVIN and TAIT. Figure lists the first prime knots with up to seven crossings;

4. Conclusion

Interlacing first appeared in mankind as a technical tool, then as a manifestation of his artistic creativity, and then many centuries after, as objects of attention for scientists, physicists and mathematicians. The development of topology and its own tools made it possible to progress in the understanding of these objects, to identify invariants. However, many issues remain open and the research is very active there. Very recently, in 2020, for example, a conjecture concerning a fascinating knot (Figure 13) discovered by John CONWAY 50 years ago has been proved by the mathematician Lisa PICCIRILLO: she proves that this knot, which possesses the same ALEXANDER-CONWAY’s polynomial as the unknot, is not a slice knot [7].

Certainly the initial hopes of THOMPSON and TAITS were betrayed because the assumptions on which they were based were proved to be wrong, but work on knots and braids has now various applications, in biology as one would expect, but also in robotics for example. Topology is not an object of secondary education and this is also not the case for graphs for many students, but the various experiments that were carried out on drawing knots in elementary school, proved to be very motivating and enriching for the students, allowing them to unexpectedly put mathematics to their service when gazing on the world and artistic creations. The entrelacs.net site bears witness to this. For the teacher’s perspective, gaining insight into the underlying mathematics is as well important and that’s the subject of this vignette.

- JORDAN’s theorem expresses that any simple and closed curve of the plane delimits two connected components of the plane, one limited, the other not.

- Standing for HOSTE, OCNEANU, MILLET, FREYD, LICKORISH, YETTER and PRZYTYCKI, TRACZYK.

References

- A. Aubin. Nœuds sauvages imaginary.org.

- L. H. Kauffman. Knots and Physics. 4th Ed, volume 53. Singapore: World Scientific, 4th ed. edition, 2013.

- M. Launay. Une énigme de 50 ans résolue : Le nœud de Conway n’est pas bordant – micmaths.

- C. Mercat. Celtic knotwork (english, french, german, spanish, italian, portuguese). http://www.entrelacs.net/.

- C.Mercat.De beaux entrelacs, video AuDiMath, Images des Mathématiques. In A. Alvarez, editor, Destination Géométrie et Topologie Avec Thurston, Voyages En Mathématiques, pages 15–26. Le Pommier, 2013.

- J.-P. Petit. Le Topologicon. Les Aventures d’Anselme Lanturlu. Belin, Savoir sans frontières edition, 1981.

- L. Piccirillo. How you too can solve 50+ year old problems – talks at google.

- D. Rolfsen. Knots and Links. 2nd Print. with Corr, volume7. Houston, TX: Publish or Perish, 2nd print. with corr. edition, 1990.

- A. Sossinsky. Knots. Origins of a mathematical theory. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1999.

Download a pdf of this article.