Originating authors are Michèle Artigue and Ferdinando Arzarello.

Originating authors are Michèle Artigue and Ferdinando Arzarello.

Given a square grid, it is easy to draw squares whose vertices are intersections of the grid lines. But is it possible to do so for other regular polygons, for instance an octagon ? The answer is : « No » and it can be proved, for the octagon, as follows (Payan, 1994) :

Let’s forget about the grid for a minute. To each regular octagon (that is, an octagon such that the sides all have the same length and all the angles are equal), we associate another octagon as indicated in figure 2. The point $A’$ is the image of the point $A$ by the anticlockwise $90^{\circ}$ rotation of centre $B$, the point $B’$ is the image of $B$ by the anticlockwise $90^{\circ}$ rotation of centre $C$, and so on… We can show that we obtain then another regular polygon, homothetic to the first one, and with same centre $O$. Its surface is strictly smaller than the surface of the first octagon.

Let’s now go back to regular polygons whose vertices are intersections of grid lines. We associate to such a polygon $P$ the number $S(P)$ of intersections of grid lines strictly contained in the polygon (i.e. the intersections which are inside the polygon but not on a side). For example, if $P$ is the pentagon of Figure 3, then $S(P)=26$ (reminder : This number is related to the surface of the pentagon by Pick’s formula Pick’s theorem ).

Figure 2 : Construction of the second polygon

Figure 3 : Computation of S(P)

Suppose now that we are able to build a regular octagon whose vertices are intersections of grid lines : $P_1$. By the process described previously we can associate to it another regular octagon $P_2$ whose vertices are also intersections of grid lines, since this property is preserved by $90^{\circ}$ rotations whose centre is a point on the grid. Moreover the integer $S(P_2)$ will be strictly smaller than $S(P_1)$. Iterating this process necessarily ends with a contradiction.

We have proved the impossibility of an octagon with vertices on grid intersections using an arithmetical method well known since Fermat’s period: a proof by infinite descent. What does this method consist in ? It consists in the impossibility of building a strictly decreasing infinite sequence of natural numbers. It relies on a property of order on the set of natural numbers : the property of being well-ordered, which means that every non-empty subset has a smallest element. Indeed, suppose that we could build a infinite decreasing sequence of positive integers $(u_n )$. Let $S$ be the set of all the terms of the sequence : $S=\{ u_0, u_1, … , u_n … \}$. Then $S$ has a smallest element, say $\alpha$. It is an element of the sequence, so there exists $k$ such that $\alpha =u_k$. But then $u_{k+1} < u_k$ and $u_{k+1}$ belongs to $S$, which contradicts the definition of $\alpha$.

Mathematical induction and the well-ordering of natural numbers

Mathematical induction, generally introduced in high school, is in fact a consequence of the well-ordering of natural numbers. It is the third of Peano’s axioms for arithmetic (1908), which is formulated as follows :

« If $S$ is a set containing $0$ and if for any element $a$ in $S$ then the successor of $a$ is also in $S$, then $S$ contains every natural number ».

We usually formulate it as follows : If a property $P$ about natural numbers is possessed by $0$ and also by the successor $n+1$ of every natural number $n$ which possesses it, then it is possessed by all natural numbers.

If we admit that the order on natural numbers is a well-ordered relation, then mathematical induction is a direct consequence. Indeed, suppose that the property $P$ is not possessed by all natural numbers, and let $S$ be the set of natural numbers which do not possess it. Then $S$ is not empty, it has a smallest element $n_0$ and $n_0$ is not $0$ since $0$ possesses $P$. Then it has a predecessor $n_0 -1$ which is not in $S$. But then $n_0 -1$ possesses $P$ and so does $n_0$, which contradicts the definition of $n_0$.

Mathematical induction can also be used to define functions. For instance, this is what we do when we define a sequence by induction, by giving a relation $u_{n+1}=f(u_n)$ where $f$ is a function defined on $\mathbb{N}$ and a first term $u_0$. We also call this a definition by induction.

Recurrence and induction : first generalization

More generally, we can think with induction on every set which is well-ordered. Consider for example the set $\{0,1\} \times \mathbb{N}$ with lexicographical order : $(a,b) \leqslant (c,d)$ if $ a < c $ or $a=c$ and $b \leqslant d$. This order is a well-ordered relation. Indeed, let $S$ be a non-empty subset of $\{0,1\} \times \mathbb{N}$, we can have two cases :

- either all the elements of $S$ are of the form $(1,b)$. Then $\{ b \mid (1,b) \in S \}$ is a non-empty subset of $\mathbb{N}$ and it has a smallest element $b_0$. Consequently $(1,b_0)$ is the smallest element of $S$ ;

- either there exists an element of $S$ of the form $(0,b)$. Then showing that $S$ has a smallest element consists in showing that $\{ b \mid (0,b) \in S \}$ has a smallest element, which is necessarily the case.

Similarly, the lexicographical order on $\mathbb{N}^p$ is a well-ordering. We leave it to the reader to adapt the previous proof to this case. Thus, there cannot be an infinite strictly decreasing sequence in these sets, even if there are infinitely many elements which are smaller than any element of the form $(a_1, a_2, … , a_p)$ with $a_1 \neq 0$ all those of the form $(b_1, b_2, …, b_p)$ with $b_1 < a_1$.

In $\mathbb{N}^p$ the principle of infinite descent which we used in the first example can be applied. And in $\mathbb{N}^p$ we can also define functions by induction. It is the case for example for the famous function from $\mathbb{N}^2$ to $\mathbb{N}$ defined by Ackermann in 1932 which we will talk about later.

Induction and ordinals

In set theory, this notion of well-ordering, which is essential for mathematical reasoning, is seen through the notion of ordinal and does not only explain well-ordering relations as seen previously. Ordinal numbers, and consequently natural numbers which are finite ordinals, are defined as well ordered sets by membership and transitivity (a set $X$ is transitive if all element $z$ of an element $y$ of $X$ is also an element of $X$), but in this article we will only see an intuitive approach of transfinite ordinals introduced by Cantor at the end of 19th century. The smallest infinite ordinal is denoted $\omega$ and is the union of all finite ordinals. It represents the order on natural numbers. It has a successor $\omega +1$ which has a successor $\omega +2$, and so on… The smallest ordinal greater than any $\omega +n$ is $\omega + \omega$ or $\omega . 2$. The smallest ordinal greater than any $\omega . n$ is $\omega^2$ and so on.

$$0, 1, 2… n… \omega, \omega+1, \omega+2… \omega+n… \omega.2, \omega.2+1, \omega.2+2… \omega.2+n… \omega.3… \omega.n … \omega^2 … \omega^3… \omega^\omega …$$

There are in fact two kinds of ordinals, those which are successors of a given ordinal, such as $\omega +n$, $\omega ^\omega +n$, for $n \neq 0$, and those which have no predecessor but are the union of all smaller ordinals, such as $\omega$, $\omega ^n$, $\omega^\omega, …$ in the previous list. We notice that the lexicographical order on $\{0,1\} \times \mathbb{N}$ gives to this set an order which corresponds to the order of the ordinal $\omega+\omega$. The generalization of the lexicographical order on $\mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N}$ corresponds to $\omega^2$, … But there are many other ordinals than those we mentioned here and every one of them is countable. It can be shown with set theory, using the axiom of choice, that any set can be well-ordered.

We can define functions by induction on ordinals. To define a function by induction on an ordinal $\alpha$, we have to give its value at $0$ and the process which allows us to obtain the value of $f(\alpha)$ from the values of the function on previous ordinals. Note that it is useful to consider two cases to define $f(\alpha)$, whether $\alpha$ is a limit or a successor. On ordinals we can proceed by infinite descent and the Goodstein vignette is a good example of such a proof.

About the Ackermann function and the diagonal argument

An example of a function defined by induction is the Ackermann function, mentioned previously. It is denoted by $A$, and is defined as follows :

- For any positive integer $y$, $A(0,y) = y+1$

- For any positive integer $x$, $A(x+1,0) = A(x,1)$

- For any pair of positive integer $(x,y)$, $A(x+1,y+1) = A(x, A(x+1,y))$.

Its value at a point $(x,y)$ is then given explicitly if $x$ is $0$. If $x \neq 0$ the computation of $A(x,y)$ uses the values of the function at some points $(c,d)$ such that $(c,d) < (x,y)$ for the lexicographical order. This computation requires a strictly decreasing sequence of such points which is necessarily finite since the lexicographical order is a well-ordering relation. However, the sequence may be very long. How many terms are necessary to find $A(3,2)$?

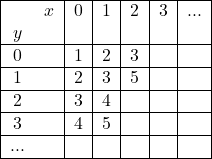

Let’s start with a simpler example : $A(2,2)$, using the following table.

The first condition $A(0,y)=y+1$ allows us to fill in the first column. Then we successively have :

$A(1,0) = A(0,1) = 2$ ; $A(1,1) = A(0,A(1,0)) = A(0, 2) = 3$ ; $A(1,2) = A(0,A(1,1))= A(0,3) = 4$, and more generally we have :

$$A(1,n+1)=A(0, A(1,n))=A(0,n+1)=n+2.$$

We can then find :

$A(2,0) = A(1,1) = 3$ ; $A(2,1) = A(1,A(2,0)) = A(1,3) = 5$ and eventually $A(2,2) = A(1, A(2,1)) = A(1,5) = 7$.

In order to find $A(2,2)$, we have to find all the values of the function for the pairs of the first column up to $(0,6)$, of the second column up to $(1,5)$, and of the third column up to $(2,2)$, i.e. we have to use $15$ values.

What happens if we want to find $A(3,2)$ and finally how much is $A(3,2)$ ? We leave it to the reader.

By fixing one of the two variables of the Ackermann function, we obtain what is generally called arithmetic functions. Thus, we write $A_n$ the function obtained by choosing the first variable to be $n$. We saw that $A_0(y)=A(0,y)=y+1$, so $A_0$ is the successor function and $A_1(y)=y+2$. We can show that $A_2(y)=2y+3$ and $A_3(y)=2^{y+3}-3$. Then, the expressions quickly become very complicated, using iterations of powers, and the values of $A(x,y)$ become very high in only a few steps. For example, $A(5,0) = 65 533$ and $A(4,2)$ is a number with $19 729$ digits.

In fact we can show that the function $g$ defined by $g(x)=A(x,x)$ is such that for all primitive recursive function, that is to say any function which can be defined with the successor function and projection functions from $\mathbb{N}^p$ to $\mathbb{N}$ by composition and induction, there is a positive integer $N$ such that $g(x) > f(x)$ for any $x$ greater than $N$. This how we prove there are computable functions which are not primitive recursive. The Ackermann function is an example of such a function. But usual functions on integers, such as functions used in secondary schools, are all primitive recursive. The functions which associate to two natural numbers their sum or product are primitive recursive. We can indeed define them by induction by : for all $x$, $x+0=x$ and $x.0=0$ and for all $y$, $x+(y+1)=(x+y)+1$ and $x(y+1)=xy+x$. We leave it to the reader to deduce that the function which associates any pair of natural numbers $(x,y)$ to $x^y$ is also primitive recursive, such as any iteration of such function. More generally, any function which can be defined using primitive recursive functions with an algorithm using a loop of the form « For $k$ from $1$ to $n$ » is primitive recursive.

The proof requires the diagonal argument. This argument was invented in 1874, by Georg Cantor, in order to prove that the set of real numbers is not countable i.e. there is no bijection between $\mathbb{R}$ and $\mathbb{N}$. In 1891, he used this method again to prove that the power set of any set $X$ (i.e. the set of all subsets of $X$) has a cardinal strictly smaller than the cardinal of $X$. The invention of the diagonal argument has been an important step in the development of mathematics. In particular it is the starting point of the proofs of many results, including Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, and of many theorems of computability theory. Russell’s paradox is also based on this idea. We can give a taste of this argument in high schools by proving that the interval $[0,1)$ is not countable, using the fact that every real number has a unique decimal representation (considering only normalized representations, i.e. we do not consider improper decimal representations ending by infinitely many $9$). Suppose there is a bijection between the interval $[0,1)$ and $\mathbb{N}$ and hence consider a sequence $(\alpha_n)$ of these real numbers. The proper decimal representation of the real number $\alpha_n$ has the form : $0$,$a_1^n a_2^n …$ , and may end by infinitely many $0$. Consider the real number $\alpha$ whose decimal representation is $0,b_1^n b_2^n …$ where $b_k=a_k ^k -1$ if $a_k ^k \neq 0$ and $b_k=a_k ^k +1$ if $a_k ^k = 0$. It is then clear that $0,b_1 ^n b_2 ^n …$ is the decimal representation of a real number $\beta$ in the interval $[0,1)$ and that $\beta$ is not equal to any element of the sequence $(\alpha_n)$. Consequently the interval $[0, 1)$ is not countable, and neither is the set of real numbers.

Conclusion

The principle of mathematical induction has been used since ancient history. For instance, in Euclid’s Elements, it is used to show there are infinitely many primes. Similarly, the principle of infinite descent has also been used for hundreds of years and is often related to Fermat who used it repetitively in his work on number theory. On the other hand, showing the equivalence of these two principles is more recent, and is due to the development of mathematical logic. The main tool for this is the notion of well-ordering in which Georg Cantor saw a « fundamental tool for thinking ». It allows us to see the equivalence between mathematical induction and infinite descent, but also to work on sets other than natural numbers and understand in particular how induction on more than one counter works (as in the Ackermann function).

The example chosen to start this vignette shows that mathematical induction is a general tool in mathematics, and not a tool only used in number theory. It plays an important role especially in discrete mathematics.

This vignette was also the opportunity to mention some important questions other than induction, but which are not independent, such as computability. The mathematisation of the intuitive notion of computability, which required the encoding of different types of discrete objects, and the use of diagonal arguments, has helped to find important results in various fields. It is also fundamental to connections between mathematics and computer science.

References

[1] Calude C., Marcus S., Tevy, I (1979). The first example of a recursive function which is not primitive recursive, Historia Math., vol. 6, n. 4, 380–84.

[2] Cori, R., Lascar D. (). Logique mathématique, tome 2 : Fonctions récursives, théorème de Gödel, théorie des ensembles, théorie des modèles. Paris : Editions Dunod.

[3] Payan C. (1992). Une belle histoire de polygones et de pixels. MATh.en.JEANS” au Palais de la Découverte, pp. 99-106. mathenjeans.free.fr/amej/edition/actes/actespdf/92099106.pdf

Very interesting.

Do you have anything about Theon from Smyrna and his diagonal numbers?

The tell the solutions to Diophantic equations in a very simple way.

Pascals triangle is reduced to a xy-table.

Theon of Smyrna’s work could be an example for this vignette. Maybe in another one !